Butter: a cook’s best friend, and the world’s most popular fat. It is the reason that the food at restaurants always tastes so good (according to Anthony Bourdain), though it has been much-maligned in the late 20th century. Revered as life-giving and associated with the sacred and pure in ancient times, this elemental food has gotten a bad reputation recently, though health experts and nutritionists are beginning to come back around to butter’s health benefits. Learn more about butter’s history, chemical makeup, and its fall from (and return to) grace among the health-conscious.

History

The earliest mention of butter is found on a limestone tablet dating back to 2,000BC. Coming from the ancient Greek bou-tyron, or “cow cheese,” butter is mentioned several times in the Bible and was regarded as a food of the gods throughout the Fertile Crescent during this time period. The earliest evidence of butter-making records were found in present-day Syria, where texts describe a “churn” made from the skin of a goat’s leg, in which the dried skin was sewed tightly together, leaving an opening at the top where cream was poured; the “churn” was then tied to a large pole and swung around “until the butter comes.” Dubious sanitary methods aside, this is surprisingly similar to the way butter is made today.

Like many innovations, similar methods of making butter were also discovered concurrently in different parts of the world, probably independently. Scandinavians seemed to have perfected butter-making first in Europe, and it spread from there. In Ireland it was common practice in the 11th through 14th centuries to mix butter with copious amounts of garlic and salt, pack it tightly into wooden containers, and bury them in peat bogs. The longer it was left in the bog, the more delicious the taste. People are still finding these ancient butter treasures today! In most cultures, butter was very expensive and precious, and as such often had nonculinary uses – in religious ceremonies in India, as a hair and nail moisturizer in ancient Rome, to treat burns and infections in ancient Egypt, and fuel for lamps in Asiatic regions. But how is it made?

Chemistry

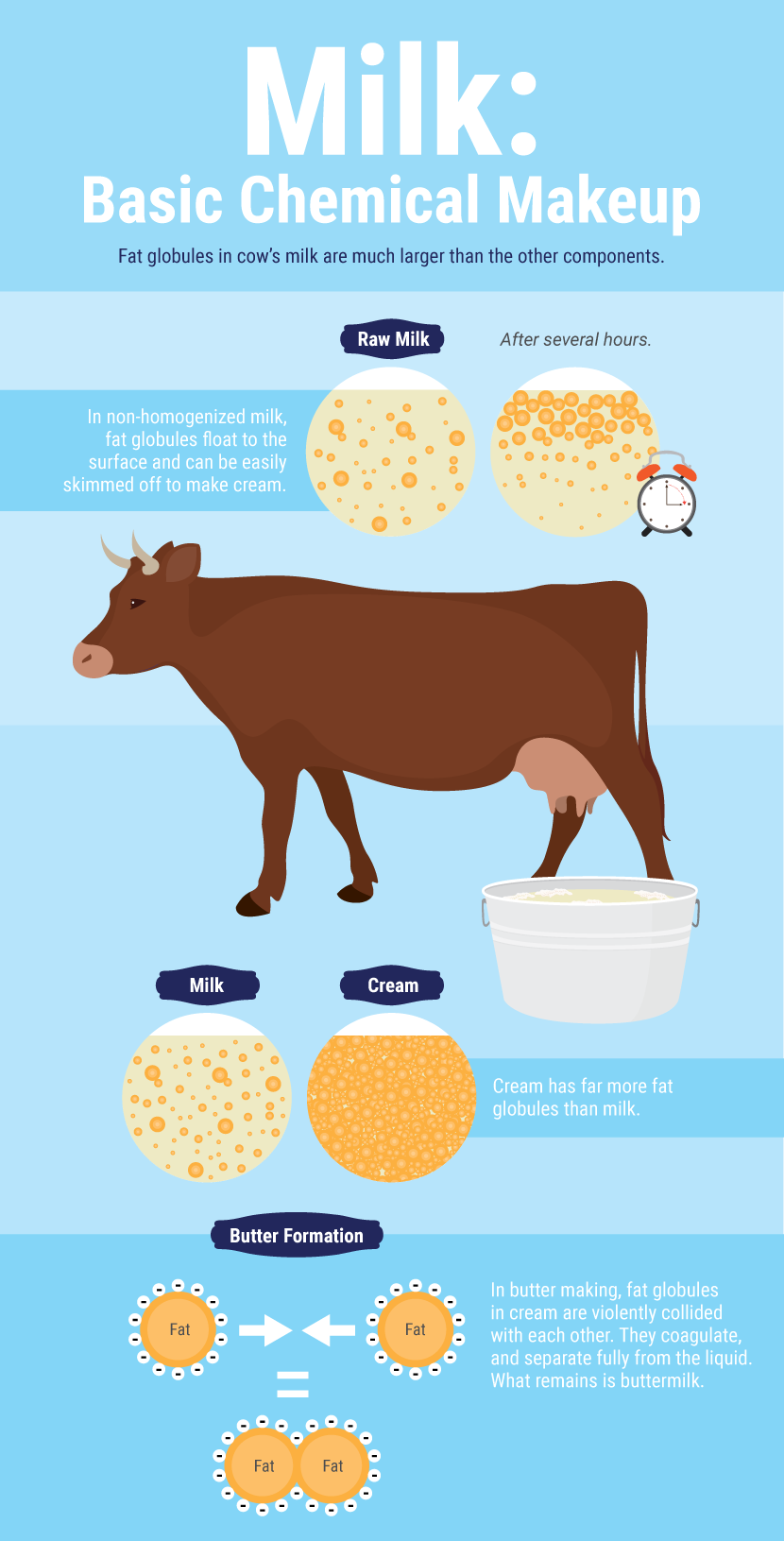

Butter is a unique substance that exists because cow (and, to a lesser extent, buffalo) milk has a very special quality: the fat globules that are suspended throughout are of a larger size than the other molecules, causing them to float; this creates a “cream line” that forms at the top when milk is left to sit still for more than a few minutes. Most milk available today is homogenized, meaning the milk has been run through a centrifuge, which prevents this cream separation; however, it is possible to find “cream line” or non-homogenized milk in certain places. This special property makes it very easy to separate most of the fat from the rest of the milk, making what we now call heavy cream and leaving what is now called skim milk, named because of the “skimming” process removing the cream requires. Cream is about 20 to 25 percent fat, while whole milk is about 10 percent or less. Sheep and goat milk do not share this property. Their milk is naturally homogenized, meaning the fat globules are the same size as the rest of the molecules and require more complicated methods to separate out (i.e., a centrifuge).

Both milk and cream are oil-in-water emulsions, which means that fat molecules stay suspended in liquid milk because they are grouped together in globules, surrounded by a thin layer of proteins that remain dissolved in the milk. Without going into too much technical detail, fats are able to stay suspended because of the natural structure of the milk and/or cream. However, it is possible to separate out those fats with a surprisingly simple method: motion.

Heavy cream has many more fat globules than milk, which explains its thick texture and velvety taste, and why it is ideal for butter making. When cream is shaken, or “churned,” the globules’ membranes smash against each other and break apart like bursting water balloons. The fat then spills out of the globules and clumps together with the other loose fats, which then begin to separate from the water. As this process continues, two new substances are formed: the solid butter and the remaining liquid, called buttermilk. The butter has now reversed itself from an oil-in-water emulsion to a water-in-oil emulsion, which means the solid fats are tightly packed together and any remaining liquid trapped in the butter is unable to separate out. We still aren’t exactly sure why churning cream makes butter, but the world is grateful for this little bit of science magic!

Cultured vs. Sweet Cream

Now that we have a basic idea of how butter is made, there are two different kinds of butter commercially available – cultured and sweet cream. Cultured is slightly more acidic and has a more tangy, “yogurty” flavor than sweet cream, which is indeed sweeter than cultured butter but contains no sugar. Cultured butter used to be made with several-days-old cream that had acidified naturally, but now cultured cream is made by adding lactic acid bacteria to the milk, which is much safer. The only difference between the two is the taste! Cultured butter has a more complex flavor, while sweet cream butter has a “flatter” flavor that works very well in cooking. Both cultured and sweet cream butter can be salted or left unsalted. Speaking of which…

Salted vs. Unsalted

The eternal question: salted or unsalted? The answer is easy. Unsalted butter is always best when used in cooking, as the amount of salt in butter varies and it’s impossible to tell exactly how much is in any given brand. This is especially important in baking, when small variations in salt can greatly affect the final product. If you want to control the amount of salt in your recipe, unsalted is the way to go. Salted butter is best when slathered on top of a slice of crusty bread!

Nutritional Debate – Butter vs. Margarine

The idea that butter is bad for you is relatively new. In the past, it was seen as an essential and delicious food, filling and rich in saturated fat, butyrate, and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and K2. In the 1950s, though, researchers found a correlation between high daily saturated fat intake and heart disease deaths. What most people don’t know is that the study’s findings were not consistent, and the author of the study cherry-picked the six countries where heart disease deaths rose along with saturated fat intake, choosing to ignore the sixteen countries where that was not the case. Yet this idea stuck, and the idea that fat is bad for you has been common knowledge for an entire generation. New research is finding no clear association between higher saturated fat intake and heart disease.

Though it’s wise to not overindulge in any rich food, it seems as though a slice of toasted sourdough topped with high-quality, farm-fresh butter is not only more delicious and satisfying than Wonderbread with margarine, it’s also the healthier choice.

How to Make Butter

Making your own butter is easy, fun, and doesn’t require much equipment! Make sure that your heavy cream is not ultra-pasteurized. Ultra-pasteurization adversely affects the proteins in the cream, making them unable to separate from the fats.

What You’ll Need

- 3 cups heavy cream (NOT ultra-pasteurized, slightly cooler than room temperature)

- Mason jar or other airtight container

- Marble (optional)

- OR stand mixer with paddle attachment (instead of jar and marble)

- Coarse sea salt

Sanitize your jar by cleaning it thoroughly, then pouring boiling water into the jar (with marble) and swishing it around. Pour out the water and let the jar and marble air-dry and cool.

Place cream and marble into jar, close jar securely, and SHAKE! Shake firmly and vigorously until cream breaks, 5 to 20 minutes. Cream will first become foamy and then butter should form. Be patient! The butter is done when it has completely separated from the liquid and forms a single clump. If using a stand mixer, beat cream with paddle attachment until butter forms. Drain buttermilk into another container and refrigerate. Knead butter under cold water (or in an ice bath) to squeeze out the last of the buttermilk. Salt to taste with coarse or Himalayan sea salt, then use, refrigerate, or make into compound butter!

Compound Butter – Herb & Garlic

Compound butter is one of the easiest things you can do to class up a dinner party – make, then spoon (or pipe) into ramekins for an impressive presentation!

- 1 cup butter, room temperature

- 2 cloves garlic, finely diced

- 1 teaspoon fresh rosemary, finely chopped

- 1 teaspoon fresh thyme, finely chopped

- 1 teaspoon fresh sage, finely chopped

- ½ tsp pepper

- ½ tsp salt, if butter is unsalted

Combine all ingredients in a bowl. Stir (or beat slowly, if using a mixer) to incorporate all garlic and herbs. Add more salt to taste if necessary.

Once you realize how easy it is to make compound butter, the options are endless! A few of my favorites are blue cheese with chives, jalapeno paprika, cinnamon sugar, and black truffle.

This article was reprinted with permission from our friends at Fix.com/blog

About the author:

Jeanine is a professional cheesemaker who teaches classes and seminars in New Jersey and New York City. Her writing on cheesemaking has recently been featured on thebillfold.com.

Jeanine is a professional cheesemaker who teaches classes and seminars in New Jersey and New York City. Her writing on cheesemaking has recently been featured on thebillfold.com.